Beautiful Graphs Increase Trust

Plus: Communicators want to increase their impact--speaking more slowly is a simple way to achieve this goal; and Persuasion is about empathy.

In this edition:

Beautiful Graphs Increase Trust.

“Communicators Want To Increase Their Impact[.] Speaking More Slowly Is A Simple Way To Achieve This Goal.”

“Persuasion Is About Empathy.”

New empirical research or polling you’re working on, or know of, that’s interesting? We’d love to hear from you! Please send ideas to hi@notesonpersuasion.com.

1. Beautiful Graphs Increase Trust

A new paper from Professors Chujun Lin and Mark Thornton finds that “independent of the quality of the underlying data,” beautiful graphs increase trust and even “predict increased citation and comment numbers.”

Specifically, the authors took 310 graphs from scientific publications, 110 graphs from news publications, and 439 graphs from social media—and then, across three studies that corresponded to publication type, “asked participants how beautiful they thought the graphs looked and how much they trusted the graphs.”

Beauty Matters Across Diverse Subject Matter and Content Types: “Across graphs of diverse content, including entertaining topics on social media, news on business, politics, health, technology, and sports, and sophisticated scientific findings across a range of disciplines,” the authors found that “the more beautiful people perceived a graph to be, the more they trusted it.” Moreover, “this association was causal: visualizing the same data in a more beautiful way caused people to trust it more,” and “the effect sizes were large and highly consistent” across subject matter and content type.

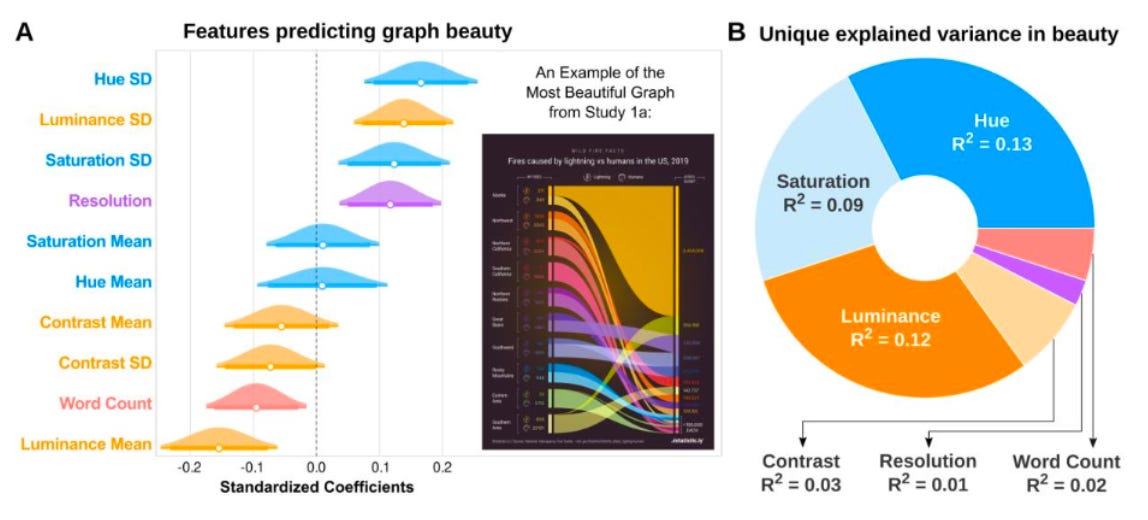

What makes a graph beautiful? “Hue, luminance, and saturation were the strongest predictors of perceived beauty … Graphs using vibrant colors were perceived as most beautiful; whereas, graphs using black, white, and red colors were perceived as least beautiful.” Here’s a chart from the authors—not in black and white—explaining the finding:

Why does beauty increase trust? Competence. “Making a graph look more beautiful caused people to infer that the graph-maker was more competent, and this inference was associated with increased trust.” Indeed, “after controlling for the effect of beauty through competence inferences, there was no remaining significant effect of beauty on trust.”

The Real-World Impact: “People’s bias in favor of trusting beautiful graphs has real-world behavioral consequences: beauty biases what information people attend to and endorse.” For example:

“The more beautiful graphs from Reddit were associated with higher numbers of comments…”

“The more beautiful graphs from scientific journals were associated with papers that had higher numbers of citations…”

But, the authors “did not find evidence that the more beautiful graphs from news reports were associated with higher real-world impact.”

Worth noting: This last result could be driven by a considerably less ideal testing environment for news sources relative to social media or scientific papers. Specifically, “because these data were not available on the news sources themselves,” the authors “approximated the news reports’ real-world impact using the counts of comments, shares, and likes about the news reports on four social media platforms [as] tracked by a third-party app.”

2. “Communicators Want To Increase Their Impact[.] Speaking More Slowly Is A Simple Way To Achieve This Goal.”

“Speaking more slowly … leads communicators to be perceived more positively,” according to a new paper from G.L Cascio Rizzo and Jonah Berger examining how vocal features influence the impact of social communications.

Evidence From Real Customer Service Calls:

How They Did It: The authors “used automated audio analysis” of “200 customer service phone calls” from “a large American online retailer” to measure how quickly employees spoke in hundreds of customer service calls.”

Finding: Speaking slowly “boosts customer satisfaction.” The authors then corroborated this finding through an experiment in which “participants were asked to imagine calling customer service for a billing issue. Then, they listened to the agent’s response through one of two professional voice recordings.”

Experimental Evidence From Voice Actors As Customer Service Agents:

How They Did It: Participants were asked to imagine calling customer service for a billing issue. Then, they listened to the agent’s response through one of two professional voice recordings. The only difference between conditions was how slowly the agent spoke.”

Finding: “Speaking slower increased customer satisfaction.”

Experimental Evidence From Doctor-Patient Interactions:

How They Did It: “Participants were asked to imagine visiting a doctor for a persistent and distressing medical condition. Then, they listened to the doctors’ response through one of two professional voice recordings. The recordings were made by a professional voice actor … The only difference between conditions was how slowly the ‘doctor’ spoke.”

Finding: “Speaking more slowly increased customer satisfaction,” which in this case means both “made communicators seem more helpful” and “like a better doctor.”

3. “Persuasion Is About Empathy.”

Neal Katyal is the former Acting Solicitor General of the United States, co-head of the appellate practice at the international law firm Hogan Lovells, and a professor at Georgetown Law School. His oral advocacy skills, honed over 50 arguments before the United States Supreme Court, have earned him praise as “masterful,” a “superstar,” —and, from one of he most prominent jurists in the country— for giving “the single best oral argument I’ve ever heard before the U.S. Supreme Court.”

In a 2020 TED Talk, Katyal credited empathy as his secret weapon for persuasion: “The conventional wisdom is that you speak with confidence. That's how you persuade. I think that's wrong. I think confidence is the enemy of persuasion. Persuasion is about empathy.” And here’s Katyal describing how—with a little help—he embraced empathy to help him prepare for his first argument before the U.S. Supreme Court:

“I flew up to Harvard and had all these legendary professors throwing questions at me. And even though I had read everything, rehearsed a million times, I wasn't persuading anyone. My arguments weren't resonating.

I was desperate. I had done everything possible … and it wasn't going anywhere. So ultimately, I stumbled on this guy—he was an acting coach, he wasn't even a lawyer. He'd never set foot in the Supreme Court. And he came into my office one day wearing a billowy white shirt and a bolo tie, and he looked at me with my folded arms and said, ‘Look, Neal, I can tell that you don't think this is going to work, but just humor me. Tell me your argument.’”

So I grabbed my legal pad, and I started reading my argument. He said, ‘What are you doing?’ I said, ‘I'm telling you my argument.’ He said, ‘Your argument is a legal pad?’ I said, ‘No, but my argument is on a legal pad.’ He said, ‘Neal, look at me. Tell me your argument.’ And so I did. And instantly, I realized, my points were resonating. I was connecting to another human being. And he could see the smile starting to form as I was saying my words, and he said, ‘OK, Neal. Now do your argument holding my hand.’ And I said, ‘What?’ And he said, ‘Yeah, hold my hand.’ I was desperate, so I did it. And I realized, ‘Wow, that's connection. That's the power of how to persuade.’”

Berger and Cascio Rizzo, the authors of the speaking slowly study, make similar points on the role of empathy during social interactions. Specifically, the authors theorized that speaking slowly would increase empathy during social interactions, which in turn, would increase persuasion:

“We suggest this possibility based on research on empathy. Empathy is commonly described as one’s ability to understand and share the concerns of another. It can involve seeing things from others’ point of view, imagining oneself in their place, or even feeling what someone else is feeling. Not surprisingly, empathy plays a key role in social interactions. Whether calling customer service, talking to salespeople, or seeking help from doctors, people want to be listened to and understood. Consequently, the more empathetic communicators seem, the more favorably audiences tend to respond.

Seeing employees or public representatives as empathetic makes consumers more satisfied with services, for example, more likely to buy products, and more likely to adopt prosocial behaviors. Perceptions of empathy are influenced by different cues. Mirroring another’s facial expression, for example, suggests that someone is experiencing the same emotions as their interaction partner. Similarly, employees’ use of personal pronouns can indicate more personal concern about a situation, and thus increase perceived empathy. And gestures depicting train of thought (e.g., pointing and shrugging), concrete language, and providing feedback are all cues that signal listening.”

The results from the study proved the hypothesis: “speaking slowly is a cue for empathy because it “signals that communicators understand and care about their audience’s needs.” Indeed, when the authors directed the voice actors role playing doctors and customer service agents to include more direct verbal expressions of empathy, the slowed rate of speech didn’t pack the same persuasive punch. It didn’t need to—the audience didn’t need to look for empathy cues indirectly because the cues came directly through the content of the message.