The Wrong Slogan Can Decrease Support For A Ballot Measure: Evidence From An In-Survey Randomized Controlled Trial

And: A poll on abortion rights; a new study on debunking misinformation; research on the effect of endorsements from special interest groups.

In this edition:

SPOTLIGHT: Choosing the wrong slogan can decrease support for a ballot measure: Evidence from an in-survey Randomized Controlled Trial.

A poll showing: “Broader Support for Abortion Rights Continues Post-Dobbs.”

A meta-analysis finding: “Attempts To Debunk Science-Relevant Misinformation” Are “On Average, Not Successful.”

New Study: Everyone knows that voters use endorsements from special interest groups to hold elected officials accountable—except, maybe they don’t.

New empirical research or polling you’re working on, or know of, that’s interesting? We’d love to hear from you! Please send ideas to hi@notesonpersuasion.com.

SPOTLIGHT: Choosing The Wrong Slogan Can Decrease Support For A Ballot Measure: Evidence From An In-Survey Randomized Controlled Trial.

There are two interrelated recognitions that are starting to reshape the first responder services that cities and counties rely on to address mental health crises:

There is a growing recognition that police officers are not the best-equipped professionals to respond to most mental health calls, a fact that’s often amplified by police officers themselves and made more urgent by the inability of police departments around the country to fill open officer positions.

At the same time, dozens of jurisdictions across the country have launched civilian mobile crisis response teams, led by clinicians or other trained mental health experts—and those programs are both improving care and reducing the load on police officers, jails and emergency rooms.

These two recognitions have created momentum for mobile crisis teams over the past few years, which has translated into local governments taking direct action to launch these programs in places like Albuquerque, Austin, Denver, Harris County, and Oakland. In other jurisdictions, though, advocates are growing impatient waiting for legislative bodies to act—and are contemplating ballot measures to bypass elected officials and go directly to voters.

Ballot measures often are messaged through slogans that act as framing devices and condense the spirit of the proposed action. For mobile crisis responder programs, there are at least three such slogans that advocates have deployed in different jurisdictions—“treatment, not trauma”; “care, not criminalization”; and “care, not cops.”

We partnered with Blue Rose Research to test the relative persuasive effect of five potential slogans—the three referenced above plus two additional ones—in support of the hypothetical ballot measure.

Between June 17-19, 2023, Blue Rose collected 12,669 surveys of likely voters nationally using both an in-survey Randomized Controlled Trial and a max-diff design.

Results from The In-Survey RCT:

We tested five messages in support of a hypothetical ballot measure (“Measure A”). Each message was tested in a randomized controlled trial environment and evaluated on support for the ballot measure. Here’s a description of the ballot measure for which respondents indicated their support or opposition:

“Some citizens have proposed adding Measure A to the ballot in the upcoming election in your city. Measure A would create a clinician-led mobile crisis response team composed of trained mental health professionals and EMTs that are part of the city's public safety plan but operate independently from the police department. When appropriate, 911 dispatchers would send these units instead of the police to handle mental health related calls for service. Based on what you know, do you support or oppose this proposed ballot measure?”

Support for the ballot measure served as the dependent variable against which the persuasiveness of each “slogan” was measured. Respondents were randomized into a group that saw one slogan that followed an otherwise consistent message:

“[Slogan]. That’s why I’m voting for Measure A, which would establish a clinician-led mobile crisis response unit composed of trained mental health professionals and EMTs. 911 dispatchers would send the unarmed mobile crisis unit to handle mental health related calls for service; and, if necessary, that team can request police presence on the scene.”

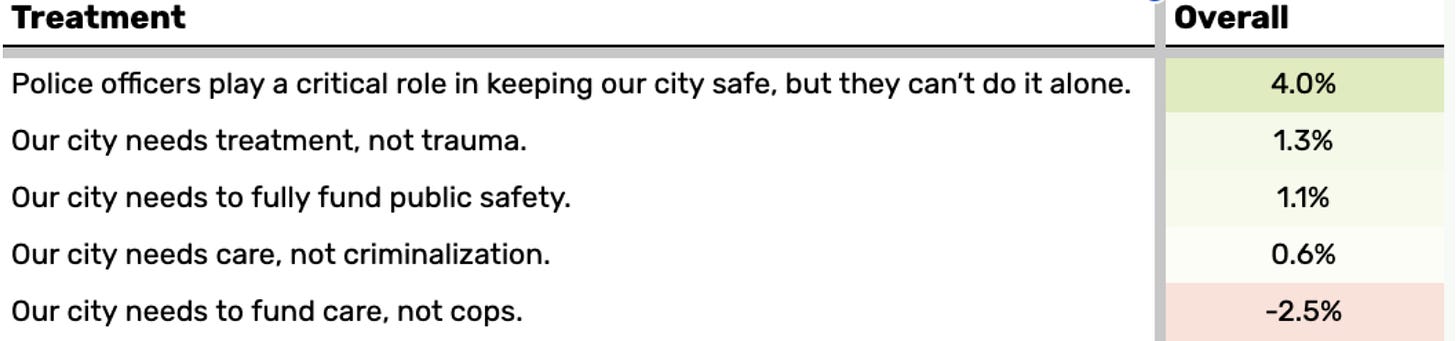

Here are the results:

The “police … can’t do it alone” message was the top performing message, increasing support for the ballot measure by 4 percentage points relative to the control group. For context, baseline support for “Measure A” was very high at 68%, which makes a four percent jump particularly notable. Notably, this is the top performing message across every sub-group (age, gender, race, ideology, 2020 presidential vote).

“Our city needs to fund care, not cops” was the worst performing message. Indeed, though intended to increase support for the ballot measure, this slogan actually decreased support for the measure by 2.5 percentage points relative to the control group.

“Treatment, not trauma” and “fully fund public safety” are neck-and-neck as the second and third best performing messages while “care, not criminalization” is roughly half as persuasive as the two messages above. Notably, however, given the high baseline support, these differences between the three messages are minor.

Results from the Max-Diff:

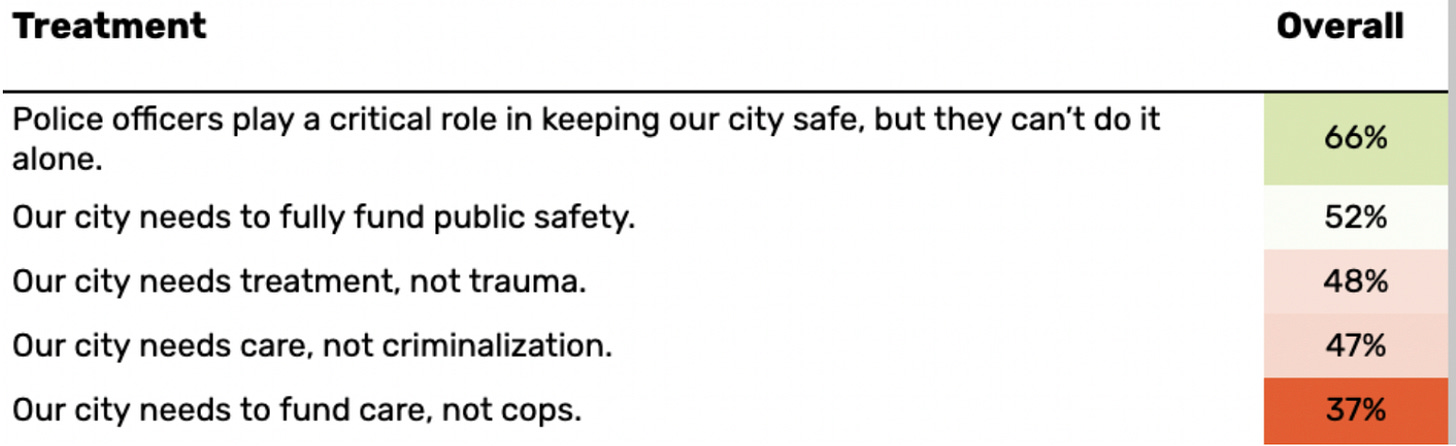

Maximum-Difference is an approach that allows messages to be ranked against each other. Each respondent is randomly served with two messages and asked to pick which one they find most persuasive. Often they will see multiple unique matchups. Then, based on this data from all respondents, we can model how often each message was selected as most compelling compared to the rest. This becomes a score of 0-100%, with 100% signifying that a message was selected over the others 100% of the time, excluding those who indicated that neither message is compelling. Scores under 50% do not necessarily reflect opposition. It just means that voters prefer these messages less relative to other messages.

Here are the results:

As with the in-survey RCT, “police…can’t do it alone” was the best performing message (indeed, again, it was the top performing message across every sub-group).

As with the in-survey RCT, “care, not cops” was again the worst performing message.

“Fully fund public safety” beat out “treatment, not trauma” by a four percentage point margin. “Care, not criminalization,” again finished in second to last place, but unlike in the RCT, it finished neck-in-neck with “treatment, not trauma.”

Takeaway:

We cross-referenced the in-survey RCT with the max-diff to corroborate the persuasive effect of each message across different testing modalities. Here are our main takeaways:

Baseline support for a ballot measure to create a mobile crisis response team is high among likely voters nationally (68%). That support is robust enough that it remained at 60%, including a majority of 2020 Trump voters, even among respondents who read a powerful opposition message to the measure (and did not read any message in support of the measure)—“I’m voting against Measure A which would establish a clinician-led mobile crisis response unit that is not part of the police department. Keeping our streets safer requires more police officers, not fewer of them. When situations turn dangerous—and especially when guns are involved—you need an armed officer, not a social worker, to ensure that no one is injured or killed.”

“Police … can’t do it alone” is worth testing as a slogan for any campaign pushing for a mobile crisis response program. “Treatment, not trauma” and “fully fund public safety” are also worth testing. Each of these messages are likely to increase support for establishing a mobile crisis response program.

These slogans are relevant beyond the context of a mobile crisis response ballot measure. Indeed, advocates used “treatment, not trauma” and “care, not criminalization” across a range of criminal justice related topics—and even in the context of fighting against this year’s proposed New York state budget. To both better capture the full persuasive potential of these potential slogans, and to test the durability of the slogans across contexts, future research should retest the slogans across a range of issues, particularly ones with more evenly divided baseline support.

Here are the full results.

THREE ITEMS WORTH YOUR TIME:

1. Poll: “Broader Support for Abortion Rights Continues Post-Dobbs.”

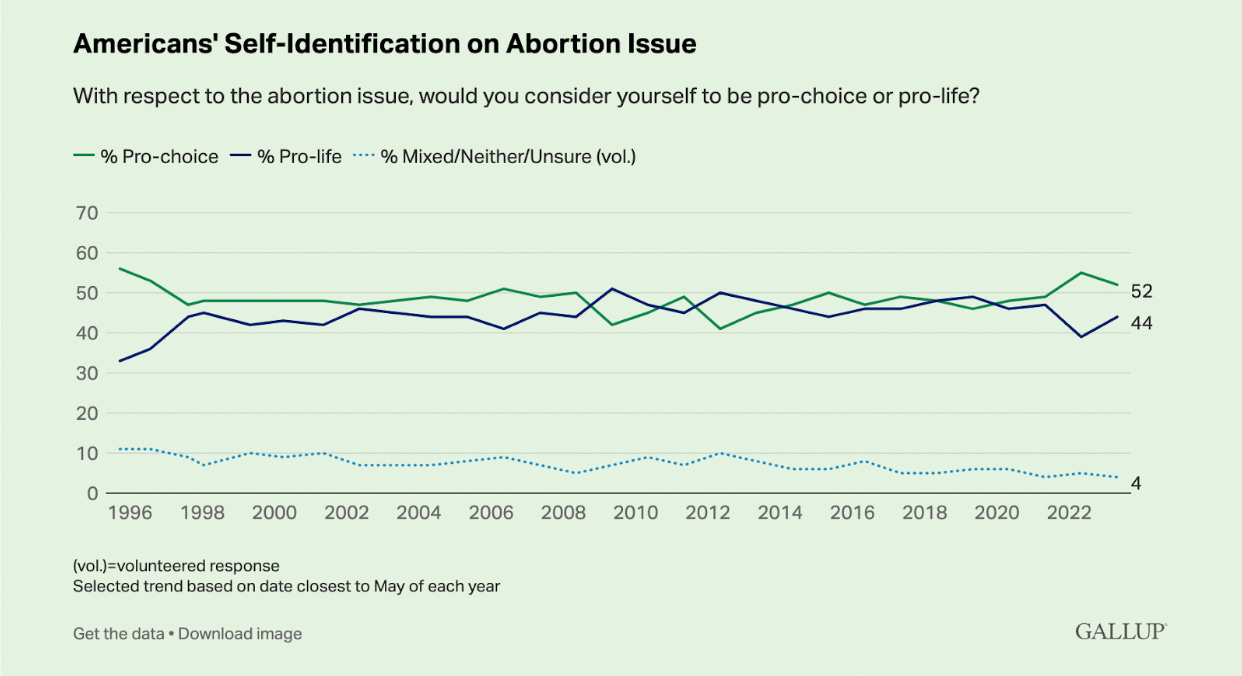

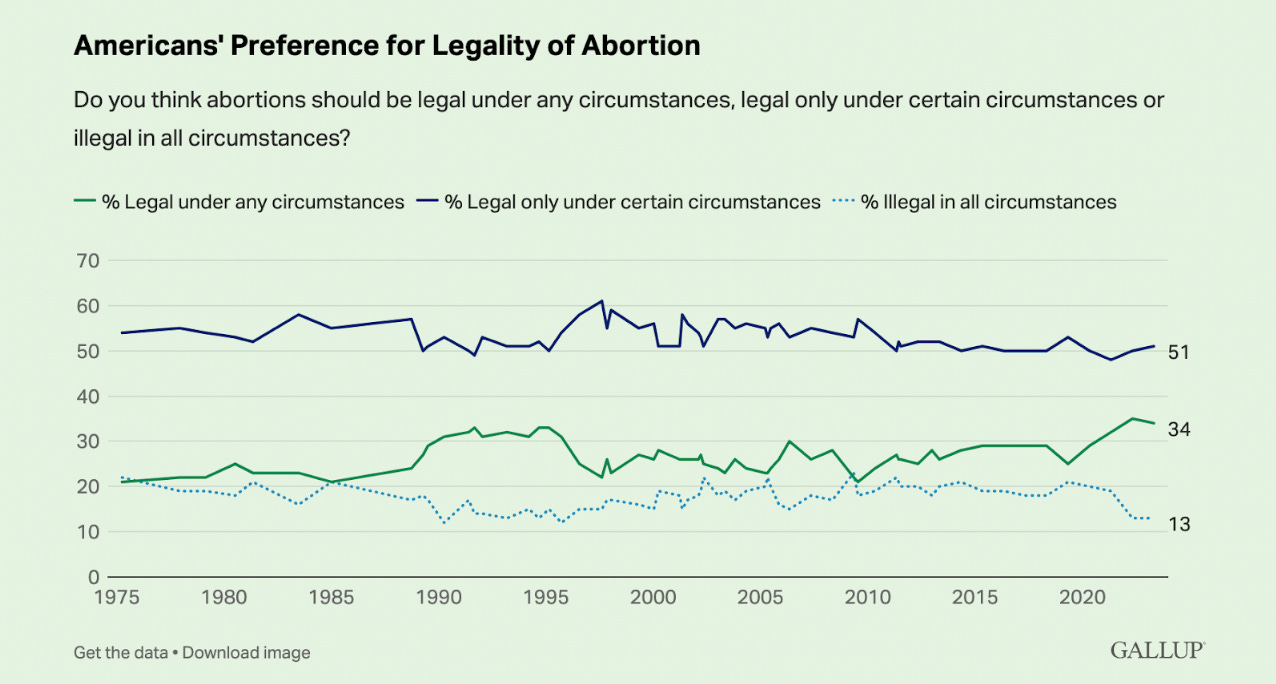

Last June, in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the United States Supreme Court, overruled Roe v. Wade, holding that the U.S. Constitution “does not confer a right to abortion” and “the authority to regulate abortion is returned to the people and their elected representatives.” In the year since the decision, Dobbs has had a sizable and lasting impact on public views of abortion rights. Indeed, according to a new 2023 Gallup poll, even “after rising to new heights last year, Americans’ support for legal abortion remains elevated in several long-term Gallup trends”:

“In most years from 1997 to 2021, Americans were closely split in their self-identification on the abortion issue, with 47%, on average, calling themselves “pro-choice” and 45% “pro-life.” …. at 52%, pro-choice sentiment is still higher than it had been for the quarter century before the Dobbs draft was leaked.”

“[T]he preference for abortion being legal under any circumstances has swelled, rising from 25% that year to 32% by 2021 and 35% in 2022. It is currently 34%. Meanwhile, the percentage of Americans wanting abortion illegal in all circumstances has fallen from 21% in 2019 to 13% in 2022 and 2023.”

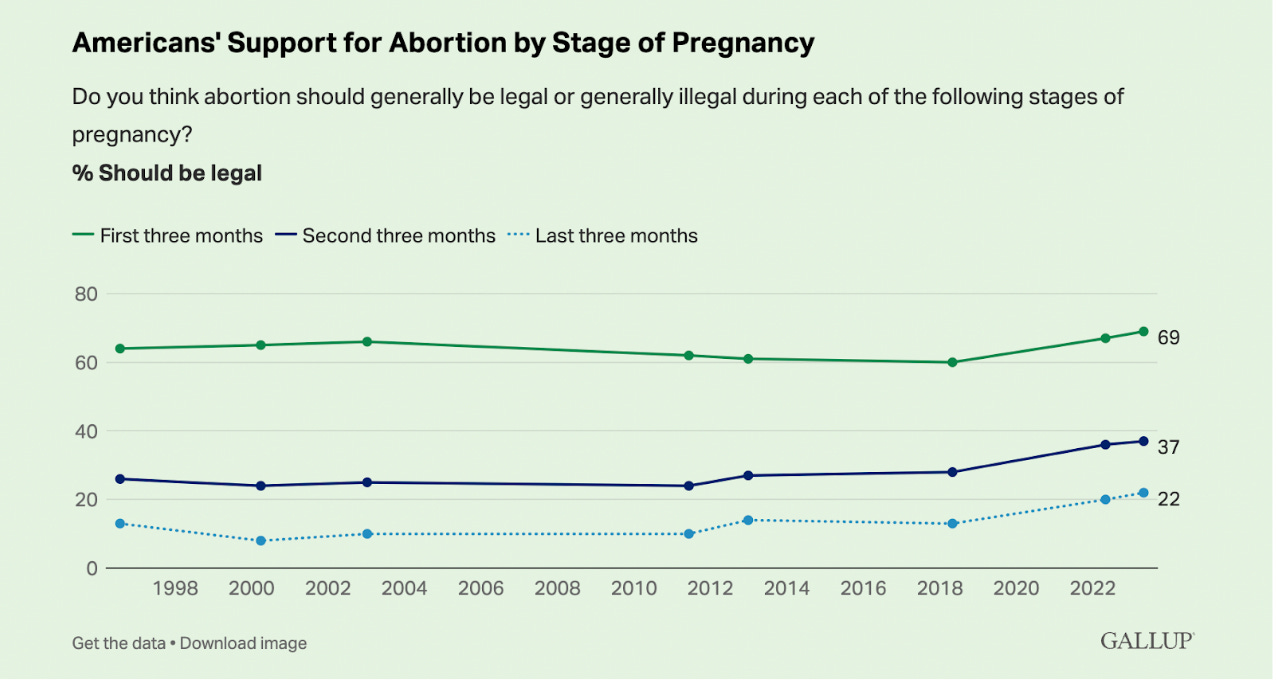

“Americans’ views on the legality of abortion have long differed depending on the stage of pregnancy in which the procedure would occur. That continues today, with 69% saying it should generally be legal in the first three months, 37% in the second three months, and 22% in the last three months. All three figures are the highest for their respective trends[.]”

2. New Meta-Analysis Finds “Attempts To Debunk Science-Relevant Misinformation” Are “On Average, Not Successful.”

Here’s a very high level overview from the University of Pennsylvania Annenberg Public Policy Center of the research on attempts to debunk misinformation about the coronavirus (for example, “the coronavirus vaccine contained microchips to track citizens”) published in Nature by Professors Man-pui Sally Chan and Dolores Albarracín: “The authors conducted a meta-analysis, a quantitative synthesis of prior research, which involved 60,000 participants in 74 experiments. Each experiment either assessed belief in misinformation about science or introduced misinformation about science as accurate and then introduced corrections for the misinformation … [Unfortunately], on average the corrections failed to accomplish their objectives[.]

More detailed findings from the study authors:

“To what degree can the public update science-relevant misinformation after a correction? … We showed that science-relevant misinformation is particularly challenging to eliminate. In fact, the correction effect we identified in this meta-analysis is smaller than those identified in all other areas.

What theoretical factors (that is, negative misinformation, detailed correction, attitudinal congeniality of the correction and issue polarization) influence the impact of corrections? … We identified conditions under which corrections are most effective, including detailed corrections, negative misinformation and issue polarization. Of these, only detailed corrections had been examined in prior meta-analyses.

Our results suggest practical recommendations for undercutting the influence of science-relevant misinformation. First, to maximize efficacy, corrections should provide detailed arguments rather than simple denials. Second, corrections should be accompanied with methods to reduce polarization around an issue. For example, thinking of a friend with a different political ideology can reduce affective polarization. Lastly, corrections are likely to be more effective when recipients are familiar with the topic. Therefore, increasing public exposure to the topics (for example, general information about a subject matter) may also maximize the impact of debunking.”

3. Everyone Knows That Voters Use Endorsements From Special Interest Groups To Hold Elected Officials Accountable—Except, Maybe They Don’t.

Professors David E. Broockman, Aaron R. Kaufman, and Gabriel S. Lenz published a new article in the British Journal of Political Science that while the academic literature “often treats … as a well-established fact” the idea that “uninformed citizens can use ratings and endorsements from [Special Interest Groups] to make inferences about their representatives' actions in office,” in reality only “a very small proportion of citizens do appear to be able to infer the positions of interest groups with names that signal their positions, but such citizens and such groups are rare.”

The results are stunning:

“Respondents are only about 10 percentage points more likely to rate liberal groups as liberal than rate conservative groups as liberal. About 40 per cent responded ‘don't know’ to the question and another 15 percent gave midpoint responses, suggesting frequent ignorance about these groups. Therefore, many citizens appear to know little about the ideology of interest groups.”

And here are the authors describing their full results:

“We first showed that citizens are typically unable to determine which side of an issue an interest group sits on and tend to project their views onto them … They are, consequently, largely unable to infer what [Special Interest Group] cues indicate about what their representatives have done in office … Citizens likewise do not adjust their evaluations of their representatives upon receiving these cues in the direction traditional theories would expect; for example, when seeing a rating that indicates their representative cast a vote they disagreed with, they do not evaluate their representatives any less positively…”

New empirical research or polling you’re working on, or know of, that’s interesting? We’d love to hear from you! Please send ideas to hi@notesonpersuasion.com.